The Ships of Mallows Bay

Approximately 30 miles south of Washington, D.C., in the shallow waters of a small Maryland bay, lay the largest tangible remnants of the Maritime Administration’s (MARAD) original predecessor, the United States Shipping Board (USSB). For those who navigate in and around the waters of Mallows Bay, the spectral remains of more than 80 wooden steamships reflect a forgotten era in U.S. maritime history; still, they have survived, silently submerged with their stories for close to a century.

The popular tale “Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay” also chronicles MARAD’s roots and successive growth at the start of the twentieth century and the onset of World War I. In September 1916, in response to severe shipping shortages and disruptions created by World War I and the United States’ dependence on foreign-built and -operated commercial ships, Congress enacted the Shipping Act of 1916, establishing the USSB. The USSB was the first federal agency tasked with promoting a U.S. merchant marine and regulating U.S. commercial shipping. While the USSB initially focused on building a sizeable American merchant fleet, the United States’ entry into the war on April 6, 1917, accelerated the need for ships to support the war effort. To help meet the demand, the Shipping Board created the Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) ten days later.

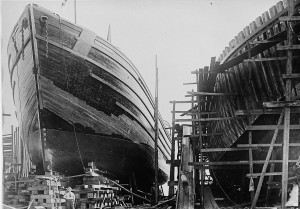

Wooden ships being constructed on the ways. Note the wooden frame of the ship on the right and the wood planking making up the hull on the left.

“Wooden ship on ways.” Glass negative. Between 1909 and 1920. Library of Congress: National Photo Company Collection.

The EFC managed this massive shipbuilding program, emphasizing the rapid construction of ships based on standard designs to counterbalance the increasing number of ships sunk by German U-boats. To address the severe shipping shortage, the EFC proposed the construction of hundreds of 240-300 foot long wooden steamships to supplement the construction of steel steamships. The EFC decided to build wooden steamships due to the abundance of lumber and doubts about whether steel production could meet the demand. While the wooden shipbuilding program was indicative of the EFC’s ingenuity and dedication to the war effort, the ships never had an opportunity to participate in the war.

By October 1918, the EFC had built 134 ships; however, when Germany surrendered the following month, essentially ending the war, the ships never crossed the Atlantic. Even though the war had ended, the EFC continued constructing wooden and steel steamships to strengthen the U.S. merchant fleet further. By July 1920, shipyards had delivered 296 wooden steamships, most of which were eventually employed in coastwise and Hawaiian trade service.

Although the wooden steamships proved themselves effective in the years immediately following the war, a combination of factors ultimately eliminated their usefulness. While the USSB had succeeded in creating a vast U.S. merchant fleet, they could not have foreseen the economic slowdown that would begin in the early 1920s, impacting the shipping market. While part of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 tasked the USSB with selling the vessels to American shipping companies to further bolster the United States’ role in worldwide shipping, the sluggish economy hampered their ability to sell them. This was particularly true of the wooden steamships, which were less desirable given the availability of newly built steel vessels. In the meantime, the USSB moored most of the wooden steamships at two separate anchorages on the James River in Virginia while looking for a buyer.

Steel and machinery being salvaged from a wooden cargo ship by Western Marine & Salvage Company, Alexandria, Virginia. “Western Marine & Salvage Co., Alex, VA.” Glass negative. 1925. Library of Congress: National Photo Company Collection. Call Number: LC-F8- 34269 [P&P]

In September 1922, Western Marine and Salvage Company (WM&SC) purchased more than 200 of the wooden steamships and moved them to the Potomac River near Widewater, Virginia. The company initially planned to tow each vessel to Alexandria, Virginia, remove any machinery, and tow it back to Widewater, where they would burn the hull, leaving only the metal fittings behind for further salvage. As the company began its operation, local watermen increasingly complained that the disposal process damaged the area’s abundant marine life and that the sunken wrecks posed hazards to navigation. The complaints eventually led WM&SC to suspend disposal operations. In April 1924, the company purchased a large tract of land on the opposite side of the river at Mallows Bay in Maryland for a new scrapping site.

Wooden ships owned by Western Marine & Salvage tied together, likely on the Potomac or at Mallows Bay.

“Western Marine & Salvage Co.” Glass negative. 1925. Library of Congress: National Photo Company Collection. Call Number: LC-F8- 35368 [P&P]

However, the move to Mallows Bay did not solve the company’s problems, as new protests now came from Maryland watermen. To avoid relocating the ships again, the company began disposing of the vessels more quickly, most notably on November 7, 1925, when 31 ships were set aflame at once, and their burned-out hulls were towed further into the bay for salvaging. However, disposing of ships en masse did not become the standard procedure, and the salvage operations returned to their slower pace. They continued until 1931, when the plummeting price of scrap metal forced WM&SC to suspend their work and ultimately declare bankruptcy. Though WM&SC ceased to exist, many beached and sunken vessels remained in Mallows Bay, scavenged for scrap by locals and inhabited by wildlife.

The United States’ entry into World War II in 1941 revived the government’s need for scrap metal, and a large amount still remained at Mallows Bay. In 1942 the government contracted with the Bethlehem Steel Corporation to recover an estimated 20,000 tons of iron from the wrecks in the bay. However, the operation was too complicated and costly even for a company as powerful and efficient as Bethlehem Steel. In September 1944, Bethlehem halted the salvage effort, leaving more than 100 vessels in the bay.

Aerial photograph of wrecks at Mallows Bay taken by Army Air Corps in 1936.

Photograph No. 18-AA-70-44; “Mallows Bay, MD.” April 8, 1936; “Airscapes” of American and Foreign Areas, 1917 – 1964; Records of the Army Air Forces, ca. 1902 – 1964, Record Group 18, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that salvage efforts were again proposed. In 1968, Congress ordered the vessels destroyed but reversed course when Congressional hearings revealed that a private company owning property around the bay sought to benefit from removing the hulks. More importantly, testimony by the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, National Audubon Society, and U.S. Department of the Interior also demonstrated that the wrecks had become an integral part of the local ecosystem and were actually benefiting the environment. These organizations argued that leaving the wrecks in Mallows Bay would protect the environment flourishing at the site and prevent pollution caused by a disposal process.

In the 1980s and 1990s, efforts were undertaken to study and document the wrecks at Mallow’s Bay. In addition to the wooden ships built for the EFC, researchers also discovered a variety of other vessels, including eighteenth-century schooners, a Confederate blockade runner, a Revolutionary War-era longboat, barges, and a car ferry that had been abandoned there in the 1970s. The largest wreck group, however, was from the EFC’s wooden shipbuilding program, 88 in total. In October 2015, President Barack Obama announced that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration was evaluating Mallows Bay for potential designation as a national marine sanctuary. On September 3, 2019, President Donald Trump announced that Mallows Bay-Potomac River would be the first national marine sanctuary designated by NOAA in almost 20 years. The site is jointly managed by NOAA, the state of Maryland, and Charles County, Maryland.

The USSB’s efforts to construct a fleet to support the war effort ushered in a new era of American shipbuilding and created a need for a new generation of merchant mariners to sail those vessels. The USSB’s World War I shipbuilding program provided the government with valuable experience planning and conducting a massive shipbuilding program. These lessons would prove crucial when the United States once again needed to rapidly build a merchant fleet to overcome worldwide shipping shortages and merchant shipping losses during World War II. The wrecks at Mallows Bay may not have fully served their intended purpose. However, they now serve as an important ecological habitat that preserves a significant era in U.S. maritime history.